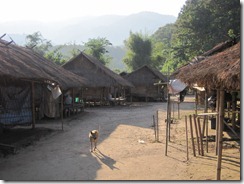

On October 24, my family and I visited a village just off the highway near Mae Chan, Thailand that was home to members of the Kayan Lahwi and the Ahka indigenous groups.

Located not far from the Burmese border, the village’s main attraction was the women and girls of the Kayan Lahwi, who wore brass coils that elongated their necks. This practice has given the group renown around the world as the “long-neck” people.

Originally from Burma, many Kayan fled to Thailand in the 1980s and 1990s following conflicts with the Burmese government. Because their legal status in Thailand is reportedly still uncertain, some have capitalized on their unique cultural practice to attract tourists who pay a steep entrance fee (400 Thai baht, or about $13.50 per adult) to take photos of and with the women and to buy their handcrafts.

The Kayan women I met spent much of their time making hand-woven scarves. They willingly let tourists take photos, although some younger women looked uncomfortable. We tried to be sensitive and asked permission before taking photos. Other tourists were not so polite and snapped away. They seemed to justify their behavior based on the cost of entry. If they paid for it, they’re entitled to it, or so they thought.

The entrance fee and booths that featured the women gave the village a carnival air. Some international organizations and human rights groups have questioned the humanity of these tourist attractions and whether they exploit the indigenous. The sentiments among the Kayan themselves seemed mixed; at least as far as I could ascertain from the meager English we exchanged and body language. Some women seemed happy and content, while others were clearly uncomfortable with gawking tourists. I noticed that younger girls no more than 14 years old were more reserved. Without a doubt, these youths bear a heavy responsibility being the primary breadwinners for their families. The majority of tourists who visit come to see them.

After I lifted a sample brass coil that must have weighed five pounds, I asked one girl what it was like to wear one. She told me that it was heavy and hot. Some say that the practice of wearing coils is inhumane, although that falls into the murky debate over whether an ethnic tradition that has existed for centuries or millennia is a violation of human rights. The coils and traditional dresses made the women more noble and unforgettable with a beauty that could only be found among the Kayan. Their presence overshadowed us tourists. I imagine that tourists like me with an oversize backpack that made me look like a tortoise were a strange sight to them.

Men were almost nowhere to be seen, although I snapped a photo of a man driving a motorcycle with children playfully chasing him. The banana trees and rice fields nearby indicated that the men spend much of their time growing food.

In the end, we paid the entrance fee and bought some souvenirs, including a hand-woven scarf, in the hope that the money raised would directly benefit the Kayan. No matter their situation, I was grateful to have had the opportunity to meet them, learn more about their culture, and take away something to remember them by.