Wat Chaiwatthanaram in Ayutthaya, Thailand

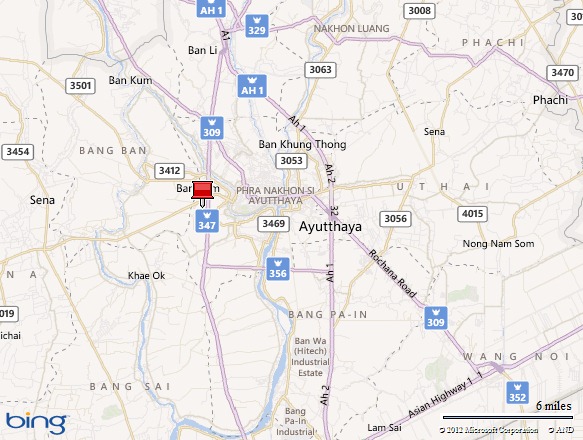

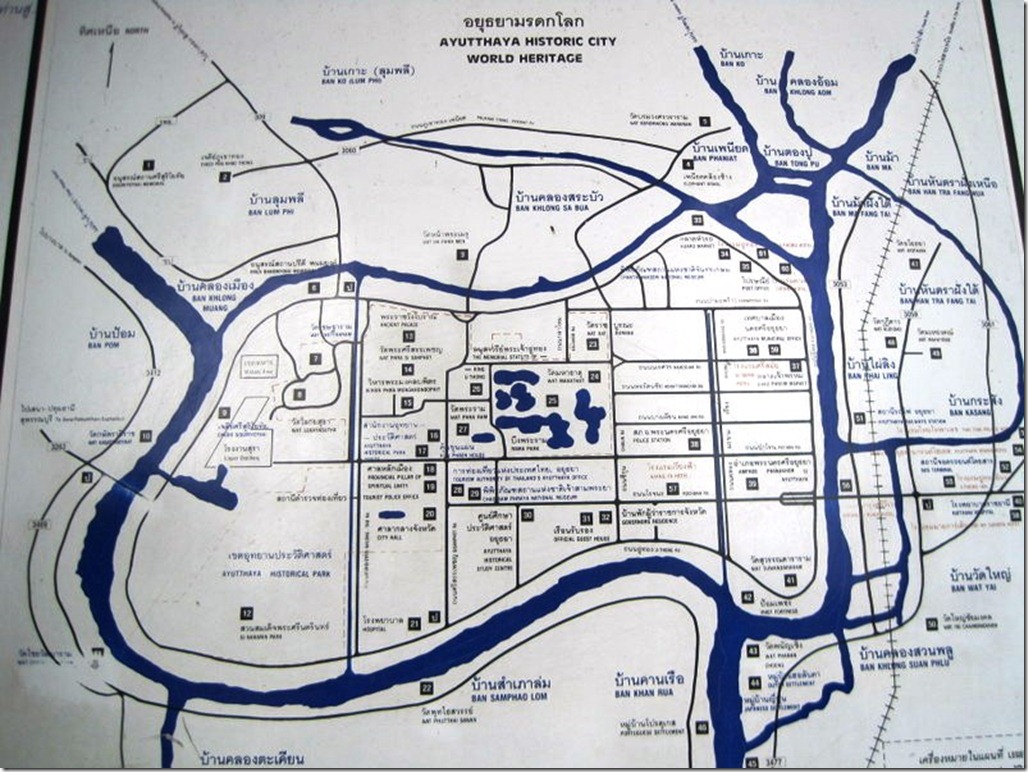

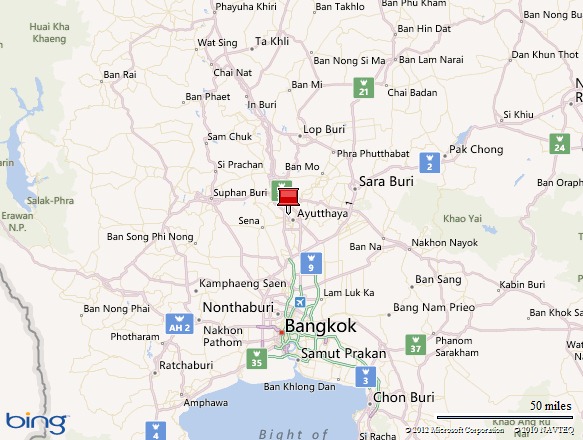

This is the second in a five-part series on Ayutthaya, Thailand about the temple ruins at Wat Chaiwatthanaram. The first article described the City of Ayutthaya. The remainder will feature other sites in Ayutthaya Historical Park, including Wat Phu Khao Thong, Wat Mahathat, and Wat Yai Chai Mongkon.

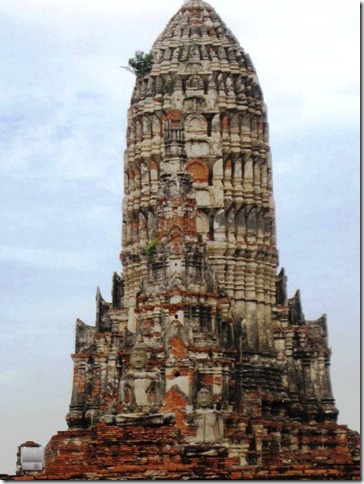

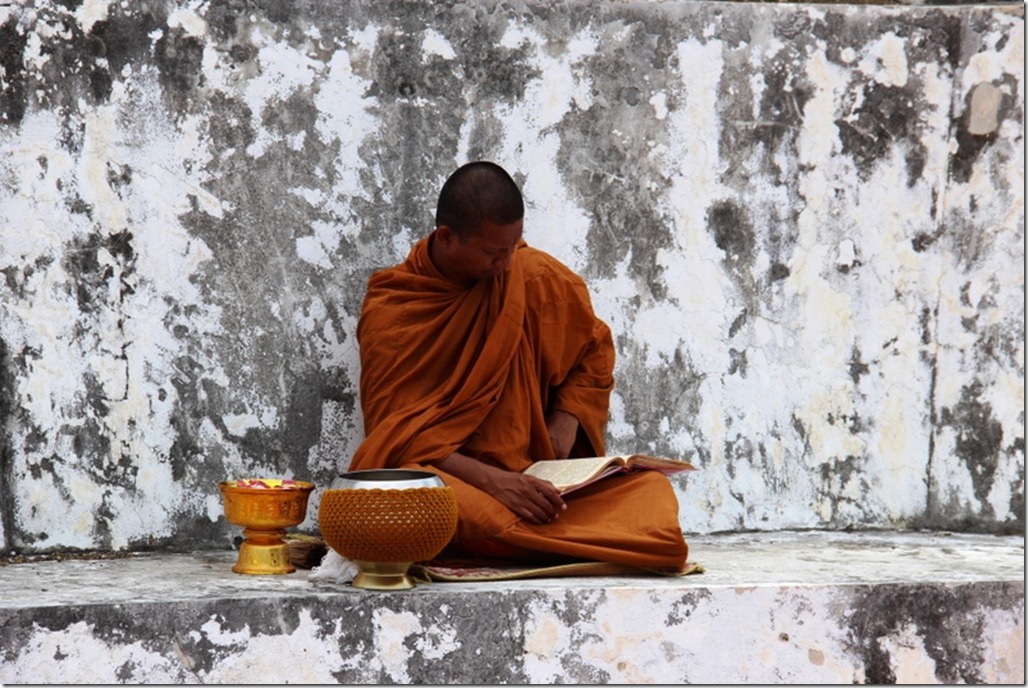

Wat Chaiwatthanaram is a restored Buddhist temple on the west bank of the Chao Phraya River across from Ayutthaya Island. In 1991, UNESCO designated the complex a World Heritage Site in Ayutthaya Historical Park. The temple ruin, one of Ayutthaya’s most popular tourist destinations, offers picturesque views that capture the essence of this fascinating place. The site is remarkable for its once-innovative square chedi or stupa (pagodas) with indented corners that are now common structures in contemporary Thai Buddhist temples.

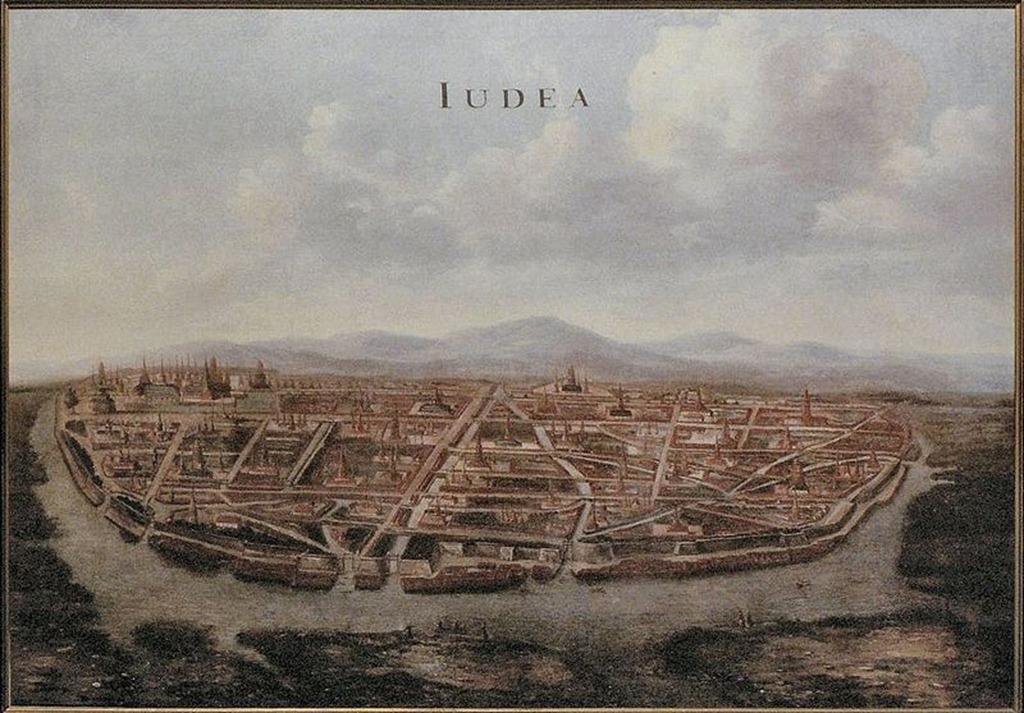

According to the information resource History of Ayutthaya, the name Wat Chaiwatthanaram is roughly translated as the “Monastery of the Victorious and Prosperous Temple.” It was built over two decades from 1630 to 1650 by King Prasat Thong of the Ayutthaya Kingdom. Dedicated to the memory of his beloved foster mother, the temple was used to perform royal ceremonies, including the cremation of deceased royals.

The temple’s centerpiece is the “Phra Prang Prathan,” a 35-meter tall prang (tower) built in Khmer (Cambodian) style popular at the time of construction.

The rectangular outer wall and gates that once surrounding the symmetrical complex were gone when I visited in August 2012, and only the foundations and a few of the eight chedi that served as chapels remained.

The wall, which symbolized the crystal walls of the world in Buddhist lore, once enclosed a large courtyard. In its center stood a still-intact, five-pointed structure (quincunx) that included Phra Prang Prathan, a symbol of the legendary Buddhist mountain Meru (Phra Men), and four smaller prang representing four continents pointing in different directions toward the sea. The courtyard represented seven oceans.

On the angled base of Phra Prang Prathan graced by large Buddhist statues, sets of stairs climbed to what was once an ordination hall where ceremonies were performed and to a gallery that symbolized seven mountains.

Two restored Thai-style chedi next to the Chao Phraya River interred the ashes of King Prasat Thong’s mother.

Destroyed by the Burmese in 1767, Wat Chaiwatthanaram lay deserted and was looted for bricks, Buddhist statues, and other artifacts for more than two centuries until it was restored by the Royal Thai government in 1992. The site sustained damage during the flooding of Ayutthaya in late 2011, and was still closed for restoration when I visited. I managed to take some fantastic photos of the complex from the site perimeter.

While some of the temple’s splendor remains, many of its structures, statues, artwork, and the royal boat landing at the river’s edge disappeared ages ago. Enough of it has been preserved to give visitors of glimpse of its former glory.

A video clip with a 360-degree view of the Wat Chaiwatthanaram site.

More About Ayutthaya, Thailand

Click here to read about the City of Ayutthaya and the Ayutthaya Historical Park

Click here to read about Wat Phu Khao Thong, a historical Buddhist monastery

Click here to read about Wat Yai Chai Mongkhon, a historical Buddhist monastery

Click here to read about Wat Mahathat, the ruin of a former Buddhist temple

M.G. Edwards is a writer of books and stories in the mystery, thriller and science fiction-fantasy genres. He also writes travel adventures. He is author of Kilimanjaro: One Man’s Quest to Go Over the Hill, a non-fiction account of his attempt to summit Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain and a collection of short stories called Real Dreams: Thirty Years of Short Stories. His books are available as an e-book and in print on Amazon.com and other booksellers. He lives in Bangkok, Thailand with his wife Jing and son Alex.

M.G. Edwards is a writer of books and stories in the mystery, thriller and science fiction-fantasy genres. He also writes travel adventures. He is author of Kilimanjaro: One Man’s Quest to Go Over the Hill, a non-fiction account of his attempt to summit Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain and a collection of short stories called Real Dreams: Thirty Years of Short Stories. His books are available as an e-book and in print on Amazon.com and other booksellers. He lives in Bangkok, Thailand with his wife Jing and son Alex.

For more books or stories by M.G. Edwards, visit his web site at www.mgedwards.com or his blog, World Adventurers. Contact him at me@mgedwards.com, on Facebook, on Google+, or @m_g_edwards on Twitter.