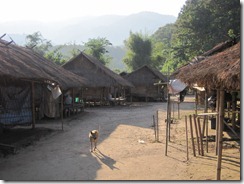

The artisan village near Mae Chan, Thailand that my family and I visited October 24 was home to members of the Akha and Kayan Lahwi indigenous groups. Two minorities that normally did not live together had joined forces to improve their livelihoods by promoting tourism and selling handicrafts.

The Akha, who lived on the opposite side of a small creek from the Kayan Lahwi, were the first people I met. Although the “long-neck” Kayan women were the primary draw for tourists who visited by the village, the Akha were the gatekeepers who collected entrance fees and ran a small motorcycle-powered ice cream cart. The cart was an odd sight in the middle of a “traditional” village, but it revealed ingenuity as yet another way for the villagers to earn extra income.

I did not realize that different ethnic groups lived together until I went back to the Akha side of the creek and noticed that the women there looked different from the Kayan. The Akha women wore distinctive headdresses bedecked with silver circlets instead of brass coils around their necks and more formal ceremonial clothing. Women who managed the market stalls eagerly tried to sell us handicrafts as we passed on our way to the Kayan side. The men I saw manned the ticket booth and parking lot at the village entrance. Tourists tended to buy arts and crafts from the Kayan, passing by the Akha’s stalls without another thought. I conjectured that the Akha were in charge of collecting entrance fees while the Kayan drew crowds. I surmised that when the Kayan fled from Burma in the 1980s and 1990s they were invited by the Akha to live and work together in order to attract tourist dollars.

One of six major hill tribes in Thailand that include the Lahu, Karen, Hmong/Miao, Mien/Yao and Lisu, the Akha have traditionally engaged in subsistence farming in a region stretching from China to Thailand, Laos, and Burma. They have come into conflict with governments and other interests over engaging in slash-and-burn agriculture and living in areas with protected ecosystems or forestlands. During my visit, I noted that the Ahka engaged in small-scale banana and rice cultivation.

I spoke with one Akha woman about life in her village. She said in English that her two children attended a public school in Mae Chan for “a better life” and that she worked to help put them through school. She did not like living there but could not move because she did not have a permit to live elsewhere. She said that life there was not easy. I was touched by her story and wondered what, if anything, I could do for her.

I’m honored that this blog has proven popular in the past week with over 3,000 visits by people searching for news about the flooding of Bangkok. I’ve continued to cover the issue because I know updates are important to those living in and around Bangkok.

I’m honored that this blog has proven popular in the past week with over 3,000 visits by people searching for news about the flooding of Bangkok. I’ve continued to cover the issue because I know updates are important to those living in and around Bangkok.