This is the second article in a series on Paraguay’s Chaco region with highlights from the area. The first focused on Filadelfia, its largest town. Other posts will feature the local Mennonite and indigenous communities. Enjoy photos and stories from one of Paraguay’s most intriguing places.

If you are looking for a trip off the beaten path, try visiting the Chaco region of Paraguay. It’s quite the trip (figuratively and literally). My family and I headed to the “Wild West” of South America, in August 2008. It’s a fun destination for those who enjoy rural tourism and exploring scenic beauty. The Chaco has many hidden gems to discover — wildlife, livestock, farmland, salt lagoons, historic battlefields, dry terrain, and the local culture.

We spent a day driving in the back country on dirt and gravel roads. We passed palm trees and lapachos (jacaranda trees) with flowers that seemed to glow in the sunlight. The flowers of different lapachos bloom at different times of the year in bright yellow, orange, or lavender. We saw Mennonite ranches (estancias) with grazing cattle and crop fields. We drove through swaths of barren land with dead trees, disheveled earth, and patches of salt residue left behind by flash floods. The water table under the Chaco is salty and non-potable, so local residents must collect and preserve as much water as they can during the rainy season (November-February) in order to weather the brutal dry season (May-August). Hollow dirt mounds serve as water reservoirs for the estancias.

We headed from Filadelfia to Isla Po’i, where we toured an experimental agriculture farm run by the Mennonites. We saw fields of cotton and mustard, two crops the Mennonites planned to introduce as cash crops.

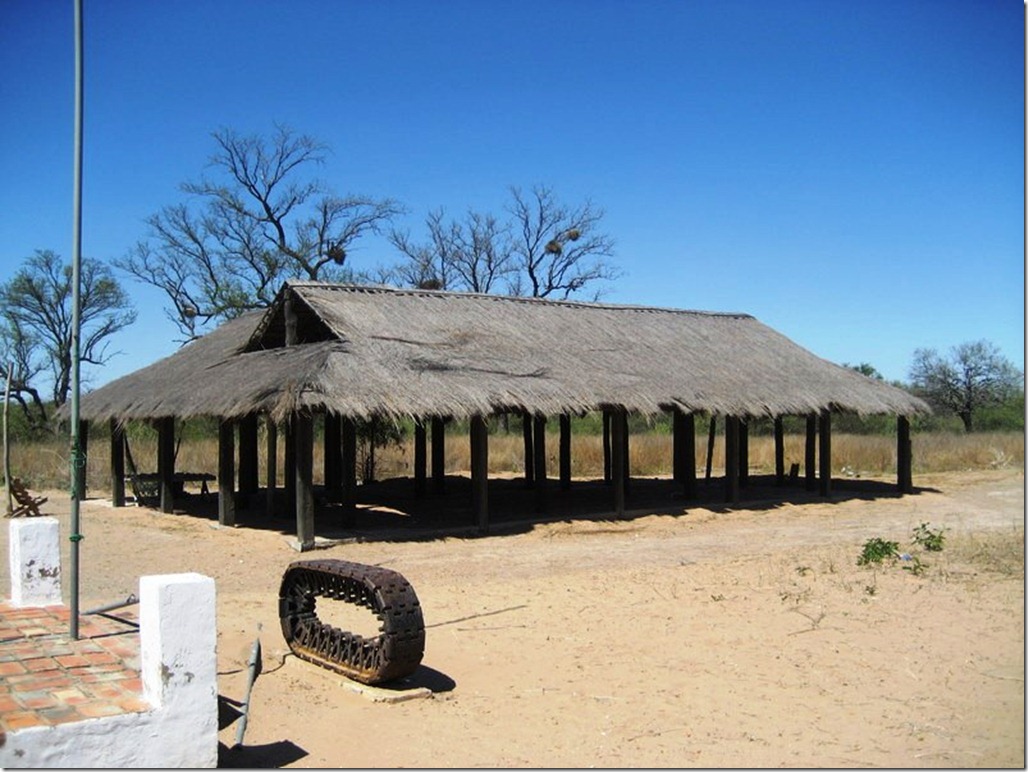

At Isla Po’I, we toured the ruins of a former Paraguayan military staging area used during the Chaco War (1932-35). The national monument is one of several dedicated to Paraguay’s victory over the Bolivians. The statue is of Mariscal José Félix Estigarribia, Paraguay’s military commander during the war and one of the country’s most celebrated heroes. The bomb shell and tank tracks were left behind by the Bolivians.

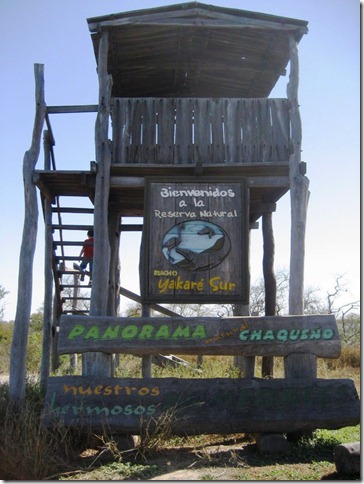

We continued on to the Yakaré Sur saltwater lagoon, a sanctuary for flamingos and other birds in the heart of the semi-arid Chaco. It’s a great place for bird watching. The view from the observation tower is gorgeous – one of the few places where you can survey the Chaco for miles in all directions.

We drove not far from Yakaré Sur to a Mennonite estancia. The scene looked idyllic with grazing cows, green pastures, windmills, and landscapes dotted with palm trees and jacarandas.

It’s easy to get lost in the back roads even with GPS, the road conditions are unpredictable, and the best places to can be hard to find. As a result, it’s advisable to hire a local guide for a half day (U.S.$90 in 2008) or full day ($150 in 2008) trip who can show you what the Chaco has to offer. Most roads are unpaved and chock full of potholes. Consider using the guide’s vehicle (an additional $150) to spare your own from wear and tear. If you drive in the Chaco, bring plenty of food and water, and be prepared for roadside emergencies. Your guide can help you navigate the myriad roads that crisscross the area.

Most of all, don’t forget to bring the tereré, a beverage made with yerba mate leaves. It’s the drink of choice in Paraguay, and you will make new friends and feel more at home in Paraguay. Enjoy a cup with your guide.

After driving more than 100 miles (160 kilometers), we opted not to visit two other attractions, Fortin Boquerón, a historic site from the Chaco War, and Fortin Toledo, home of the Tagua Reserve, a reserve for the endangered tagua boar (peccary). It’s impossible to see all the major points of interest in the Chaco in one day.

Our adventure continued when we returned to Asunción via the Trans-Chaco Highway. During the five-hour drive, we saw herds of cattle grazing amid fields of grass peppered with palm trees; fields charred by wildfires; igloo-size brick ovens; and cowboys (gauchos) herding cattle. We enjoyed taking in the wide open spaces and flatlands of western Paraguay.

If you have the opportunity to visit Paraguay and the time for a few out-of-the-way excursions, head to the Chaco. Plan to take at least four days to see sites such as Filadelfia that are easily accessible from the Trans-Chaco Highway. For more remote locations such as Cerro León (Lion Hill) in Parque Nacional del Defensores del Chaco (National Park of the Defenders of the Chaco), set aside at least a week, hire a guide, and expect to rough it.

More about the Chaco

- Filadelfia, the capital of Boquerón Province and the largest town in the Chaco

This is an update with photos of an article I posted in September 2008. Click here to read the original post.

[…] my series on Paraguay’s western region focused on Filadelfia, the area’s largest town, and the rural Chaco. The final post will highlight the local indigenous […]

[…] they face. The first post focused on Filadelfia, the area’s largest town, the second on the rural Chaco, and the third on the Mennonites. Unlike my other travelogues that emphasize tourism, this one […]